Inflation & the Party

release time : 2011-05-17 view count : 354 次

If inflation, which is mostly driven by food, rises high enough to jeopardise social stability, the Party’s policy responses would have broad consequences. A sharp slowdown in lending, for example, could lead to slower growth in construction of infrastructure and homes, leading to slower FAI growth and thus slower GDP expansion, as well as weaker demand for commodities.

In our view, we are near the peak in food-price inflation, which means we are close to the peak in overall CPI for this cycle. We are therefore sticking with our forecast of 4.5% average CPI for the year. While this is significantly higher than in recent years (roughly 3.5%), it is not dangerously high, given the rate of GDP and income growth. As a result, we believe monetary policy normalisation from the 2009 stimulus is largely complete. Credit and liquidity growth will be slower this year than last, but conditions will remain mildly accommodative.

The Party and inflation

It is not surprising that China’s Communist Party worries about inflation. CPI spiked to almost 20% in 1988 and 1989, creating both economic and political problems. As historian Maurice Meisner explains in The Deng Xiaoping Era, ‘Intellectuals did not challenge the Communist state simply because of low pay and high prices, but rapidly deteriorating living standards in the cities undoubtedly sharpened their animosity towards the Deng regime and swelled the ranks of dissidents.’

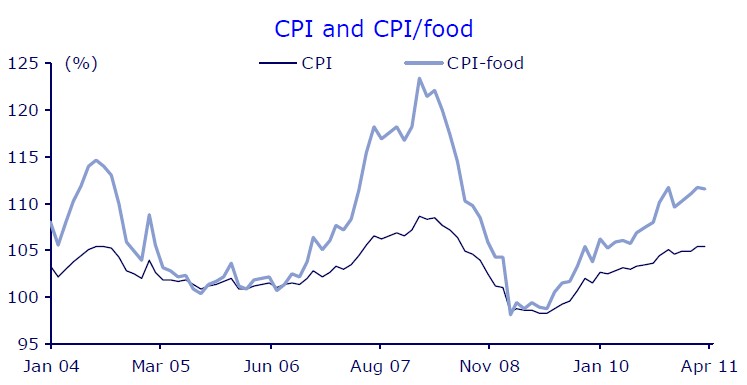

It is, however, surprising that despite a decade of 10% average annual GDP growth, CPI has not been in double-digits in China since 1995. CPI averaged 3.6% during the five years prior to the 2009 stimulus, when it was -0.7%. Core CPI (ex-food and energy) averaged 0.5% during the 2006-to-2010 period.

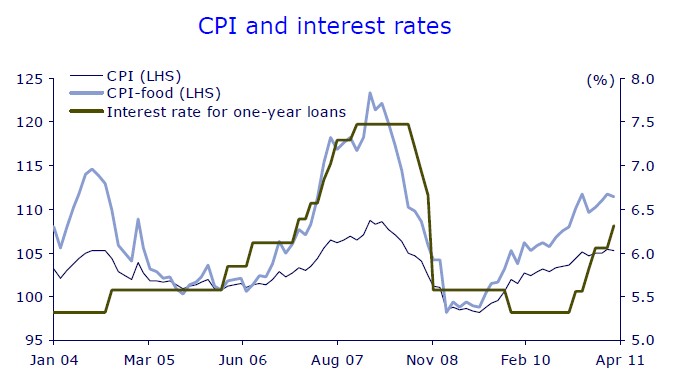

Even more surprising has been the pragmatic approach the Party has taken in dealing with the current and previous inflation spikes. After remaining below 2% for most of 2005 and 2006, CPI rose to over 6% at the end of 2007, leading some to fear a return to double-digit inflation. The Party responded by leaning on companies to temporarily freeze prices for cooking oil, milk and instant noodles, and by raising benchmark lending rates six times, from 6.12% to 7.47%.

However, it lifted the price controls after three months, and the last interest-rate hike came in December 2007, when CPI was 6.5% and CPI/food was 16.7%. CPI did not peak for two more months, hitting 8.7% in February 2008 (when CPI/food climbed to 23.3%), and did not fall below 6% until August 2008, but the Party, recognising that inflation expectations had peaked, refrained from further rate increases.

Of course, in late 2007 the emerging subprime crisis was also a significant factor restraining the Party from further rate hikes. Today, decelerating GDP growth in China (9.7% YoY in 1Q11 compared with 11.9% in 1Q10) must also be weighing on the leaders’ minds. We expect continued pragmatism as the Party attempts to manage China’s current bout of inflation.

Attack of the fresh fruit and veg

Between May and August of last year, CPI was running a little below the 3.6% average of the five pre-stimulus years, before ticking up to 3.6% in September, generating little attention. Then CPI spiked to 4.4% in October and 5.1% in November, quickly sparking fears of runaway inflation and tight monetary policy.

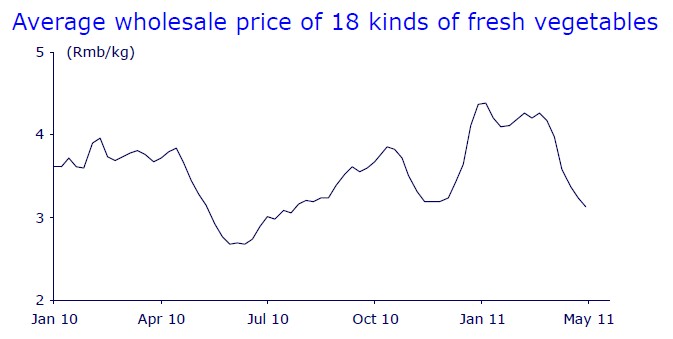

The key factor causing the CPI spike was a sharp rise in prices for fresh vegetables and fruit. Veggie prices accelerated from an 18% growth rate in September to 31% YoY in October, before cooling to 21% in November and then -6% in December. Fresh fruit prices rose 13% YoY in September, then 18% in October, 28% in November and 34% in December. We estimate that fruit and veg combined went from contributing 0.8ppts to headline CPI in September to 1.2ppts in October and November, before falling back to 0.4ppts in December.

China imports very little fruit and veg, so the key price factors are domestic. Prices for these labour-intensive goods were rising steadily as the stimulus-led economic recovery created tighter labour markets and higher wages, as farmers had to compete for workers with the construction and manufacturing sectors. But widespread bad weather across the mainland, which damaged crops and hampered transport, caused the sudden price jump. The price growth rate for fresh fruit and vegetables shot up to almost double the average rate of the previous three years. As the weather improved (and the government cancelled highway tolls for fresh food), vegetable prices cooled. With a longer growing cycle, fruit prices will take more time to recover.

The higher fruit-and-veg prices meant that overall food prices, which account for about one-third of the CPI basket, also accelerated in October and November. CPI/food leapt from 8% in September to 10.1% in October and 11.7% in November, before cooling to 9.6% in December. In October and November, we estimate that food accounted for 75% of the overall CPI increase, and fruit and veg accounted for about one-third of the CPI/food rise.

We do not believe that an increase in food demand contributed significantly to higher prices. The World Bank’s China economists, in their latest ‘Quarterly Update’, explain why:

‘It is often argued that increased demand for food and changes in diets in emerging and developing economies and resulting pressure on scarce resources such as land are key drivers of higher food prices. However, in China the changes in diet and resulting pressure on scarce resources were much more rapid in 1990-2000, when food-price increases were subdued, than in 2000-2009. Per-capita daily calorie intake rose steadily from 1960 until 2000 but then it reached a ceiling broadly at the level of high income Asian neighbours such as Japan and South Korea.’

Recent food-price trend

We have several reasons for being optimistic that while food prices will remain high, the food-inflation growth rate will cool in the coming months.

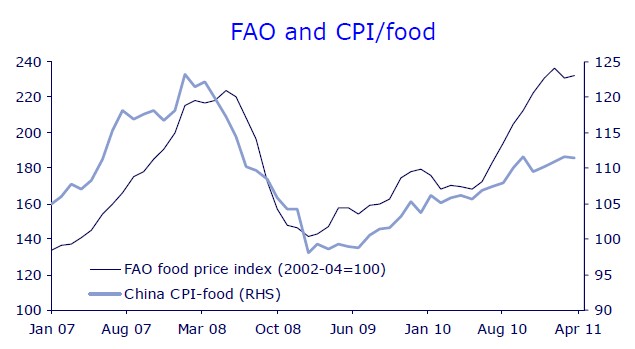

First, there are early signs that global food price growth is decelerating. After rising for eight consecutive months, the UN Food and Agricultural Organisation monthly global food price index fell from 237 in February to 231 in March, and was 232 in April.

More importantly, some food prices in China have begun to decline or decelerate. Because they were responsible for much of last year’s CPI spike, it is noteworthy that the average wholesale price of 18 kinds of fresh vegetables has declined for four consecutive weeks, including by 9.9% WoW in the third week of April and 5.7% WoW in the fourth week, 4.2% in the fifth week and 3.2% in the first week of May. Vegetable prices are down 29% from the beginning of February.

Wholesale pork prices are up 41% YoY, but have been decelerating. In the past six weeks, prices rose 1.3%, while in the previous six-week period they climbed 4.2%. Chicken prices have been flat for four straight weeks.

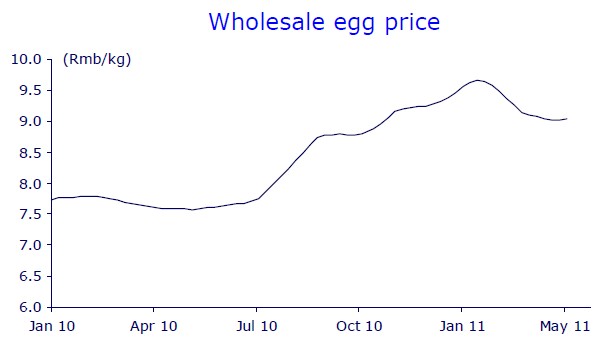

Egg prices have declined for eleven straight weeks, before ticking up 0.3% WoW during the first week of May, and are down 6.4% from early February.

Edible oil prices have been flat for the past five weeks, but in this case, the change is the result of government pressure on producers not to raise prices.

Because some food prices have been decelerating, the CPI/food index has also cooled. The following chart shows the tremendous degree of seasonality in MoM food prices in China. It also illustrates that there were several months last year and early this year when the MoM rise in prices was significantly higher than the average MoM change for the same period during the 2001-09 period. But the March 2011 MoM CPI/food index was 99, almost exactly in line with the 98.9 average from the 2001-09 period for that month, and the April CPI/food index was 99.6, back to trend.

Finally, the base effect will become an important factor in the second half of the year. CPI was much lower (average 2.6% YoY) in 1H10 than in 2H10 (average 4.1% YoY), and from July of last year, CPI/food was never below 6.8%. Thus, the combination of slower growth or declining prices MoM and a higher base will result in lower YoY growth rates in 2H11.

Food inflation, and thus overall CPI inflation, is close to peaking

We are at or close to the peak in food-price inflation, which means we are at or close to the peak in overall CPI for this cycle. We therefore are sticking with our forecast of 4.5% average CPI for the year. While this is significantly higher than in recent years (roughly 3.5%), it is not dangerously high given the GDP and income growth rates.

The key risks to this forecast are: 1) a sustained period of US$150 per barrel of oil, which would drive up global food prices via higher fertiliser and transport costs, as well as stronger bio fuels demand; 2) a sharp spike in the price of pork, China’s primary protein source, although price growth has recently been decelerating, and the hog population and piglet prices signal that supply will overtake demand by late summer, leading to lower prices; or 3) a repeat bout of widespread bad weather across China, which would cause another temporary spike in food prices.

A spike in food prices may come in June because of the base effect, but that is likely to be the peak for this year.

Gimme shelter

Aside from food, the only other part of the CPI basket where prices are rising at a significant pace is residence expenses. In 4Q10, food accounted for an average 73% of the CPI increase, while residence expenses contributed another 17% of the overall rise. In April of this year, food accounted for 64% of the 5.3% rise in headline CPI, while residence expenses contributed another 22%.

There are four main components of the residence expenses part of the CPI basket. According to information disclosed by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), last year utilities were 41% of the CPI/residence expenses index, and accounted for 51% of the 4.5% rise in this index. This was because in 2009, when the economy was growing more slowly, the government did not significantly increase charges for residential consumption of power, water and gas. But as the economy recovered and CPI remained low, it raised utility charges, generating half of the increase in the CPI/residence expenses index. Beijing, for example, raised water charges by 8% at the end of 2009.

This year, if CPI remains elevated, we do not expect the government to raise utility charges, which means their contribution to inflation will be significantly smaller. But because the NBS changed the weightings for the residential expenses index at the start of the year without disclosing the details, we will need a few more months of data before we can estimate the specific impact.

Decorating materials

The second-largest component of the CPI/residence expenses index last year was building and decoration materials, at 27%, and rising prices for those accounted for 20% of the 4.5% increase in this index. The price hikes were driven in part by a 44% jump in housing sales in 2009, which created a sharp spike in demand for the decoration materials owners used to finish their new flats (which were generally handed over as a bare bones structure). While we expect the housing market to be healthy this year, the growth rate of home sales has slowed significantly since 2009, helping keep decoration material prices fairly stable.

The third-largest component of the CPI/residence expenses index last year was private housing, with a 21% weighting. This component accounted for 17% of the 4.5% rise in this index, and included mortgage, property maintenance and management fees. This component rose rapidly in 4Q10 and 1Q11, largely due to higher mortgage costs as the central bank raised interest rates and many banks discontinued the interest-rate discounts that they had offered during the global financial crisis. We believe that the makeup of this component has been adjusted significantly since the start of this year, to include, for the first time, some form of indirect reflection of home-sale prices. Regrettably, the NBS has not offered details, but we expect this component to rise less rapidly this year because we believe the central bank has finished raising interest rates.

Rent

The fourth component of the CPI/residence expenses is rent, and last year this had an 11% weighting and contributed 12% of the rise in this index. Rents are likely to continue growing at about the same pace as last year, but the low weighting means higher rents will have a minor impact on the overall CPI/residence expenses index.

To sum up, we expect the residence expenses part of CPI to cool off this year, because the government will not raise utility charges, because the cost of decoration materials should stabilise with slower growth in housing sales, and because the central bank is done raising rates. Because of the base effect - the residence expenses index rose 3.9% YoY in 1H10 and 5% in 2H10 - this cooling should be apparent within a couple of months.

Outside of food and shelter, very little inflation

CPI excluding food and residence expenses rose 1.2% in April, 1.1% in March, 0.9% in February and 1% in January. In 2H10, CPI ex-food and residence rose in the range of 0.7% to 1.1%, up significantly from the -0.2% to 0.3% range during 2H07, but still moderate in the context of China’s income growth.

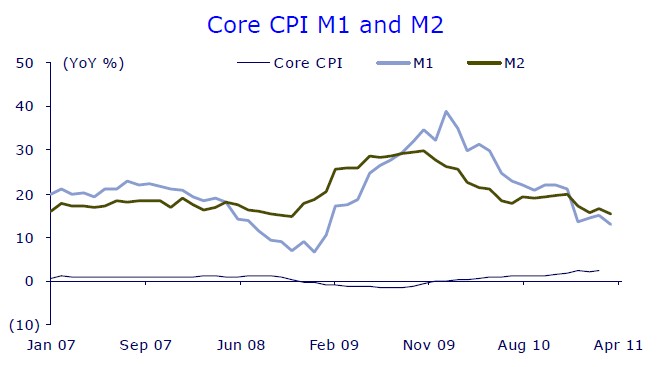

As we have noted, in April, food accounted for 64% of the 5.3% rise in overall CPI, while residence expenses contributed another 22%. The non-food, non-shelter part of the basket - about half its weight - accounted for only 14% of the CPI increase, reflecting that this round of inflation in China is not primarily a monetary phenomenon.

Not always a monetary phenomenon

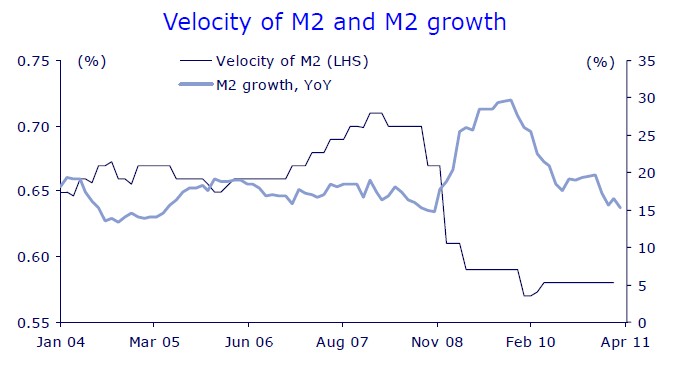

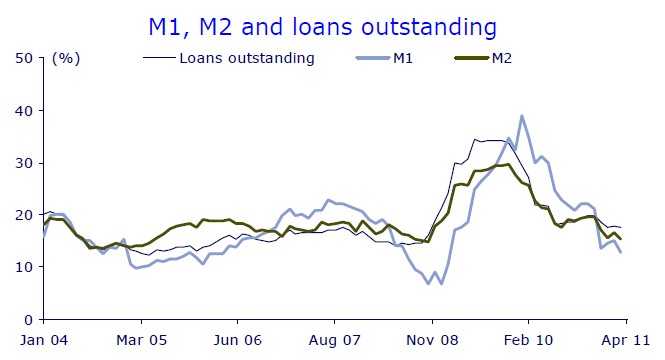

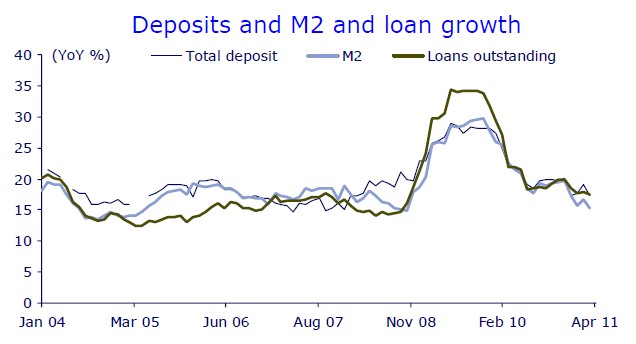

Monetary policy has played only a contributing role in the current CPI spike. As part of Beijing’s stimulus programme, money supply (M2) growth jumped from 19% in January 2009 to 28% in June of that year. But there are two reasons why inflation is not, in the short term, ‘always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon,’ especially today in China.

First, because the velocity of money (the speed at which it changes hands to buy things) fell sharply at the same time M2 rose, effectively neutralising much of the increase in supply. In other words, most of the increase in money was not out chasing goods and services, and thus was not driving up prices.

The key to avoiding monetary policy becoming a significant inflation driver is for the M2 growth rate to return to what passes for normal in China, well before the velocity of money rebounds. And that has happened, with M2 growth back to 15.3% in April and 16.6% in March, compared with 19.7% in 2010 and 27.7% in 2009.

Bringing M2 down to about 16% at the start of the year means the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has succeeded in cooling money-supply growth well before the velocity of money rebounds, mitigating much of the inflationary impact of the 2009 stimulus-liquidity surge.

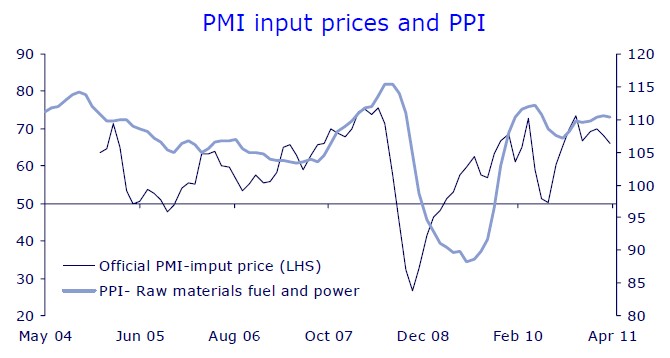

The second factor is that significant overcapacity limits the ability of Chinese manufacturers to pass on higher input costs. When, for example, the purchasing price index (PPI) for industrial inputs rose to 15.4% in July 2008 from 3.6% a year earlier, it had almost no impact on core CPI (ex-food and energy). Core CPI rose to 1.1% in July 2008 from 0.8% a year earlier, and by December 2008 it had actually fallen to -0.4%. Industrial profit growth, on the other hand, plummeted. Profits were down 27% YoY in November 2008, compared with a 33% rise a year earlier.

How nervous is the Party?

After considering the inflation scenario we have just sketched, the key question investors must be asking is: ‘How nervous about inflation is China’s Communist Party?’

On the one hand, GDP is slowing a bit, but on the other hand, CPI rose to 5.3% in April. To tighten, or not to tighten? In our view, inflation is under control and will soon peak, and further tightening is unnecessary. We believe the Party leadership shares that view and that interest rates and growth rates for credit and liquidity will hold at roughly current levels.

Inflation expectations have cooled

One important issue for the Party is inflation expectations. Studies by CLSA found that the share of middle-class consumers across the country who expected overall prices to rise peaked in October at 93%, and then fell to 69% in January (the lowest share in 15 months). Although the share rose again to 79% in March and April, the peak of consumer concern appears to have passed.

The central bank’s quarterly consumer survey found similar results. The share of consumers expecting prices to rise jumped from 46% last September to 61% in December, before falling back to 47% in March. This pattern is similar to the last time China ran into higher inflation. In December 2007, expectations peaked at 65% before falling to 49% in March, even though CPI did not peak until Februaryand did not fall significantly for several more months. Back then, consumers had visibility that inflation would soon cool off, and that appears to be the case again today.

This is important because reduced inflation expectations will leave the Party less inclined to use one of its biggest tools for managing those expectations, interest rates.

Will rising food prices lead to social turmoil in China?

Higher food prices are unlikely to result in social instability, especially if food-price inflation peaks, as we expect, in the coming months at a level well below that reached a few years ago.

The key factor is that a decade of rapidly rising income has left the Chinese far better equipped than many of their emerging markets counterparts to manage higher food prices.

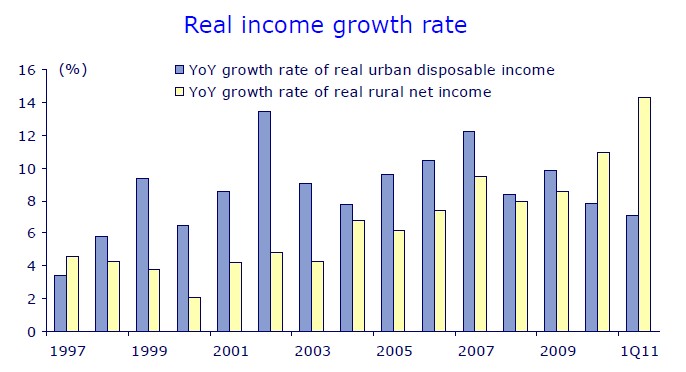

Inflation-adjusted urban income rose 7.1% in 1Q, (7.8% in 2010), and this is likely to be the eleventh consecutive year of 7% or faster growth. Real rural incomes rose 14.3%, up from 10.9% last year. This strong income growth mitigates the impact of higher food prices.

Party pragmatism and interest rates

The Party has been surprisingly pragmatic in dealing with the current and previous inflation spikes. Last time, the final interest-rate hike came in December 2007, when CPI was 6.5% and CPI/food was 16.7%. CPI did not peak for two more months, hitting 8.7% in February 2008 (when CPI/food climbed to 23.3%), and did not fall below 6% until August 2008, but the Party - recognising that inflation expectations had peaked - refrained from further rate increases.

We expect continued pragmatism as the Party attempts to manage China’s current bout of inflation. While we are not sure which month the CPI peak will come this time - March or June are most likely - we believe the peak is close enough that the Party, which is always worried about growth and employment, will stop raising interest rates now. But, even if we are wrong, and there is one more 25bps hike, there would be very little impact on the economy or on market sentiment, both because this is not an interest-rate sensitive economy and because rates are now more than 100bps below the December 2007 level.

In our view, monetary-policy normalisation from the 2009 stimulus is largely completed. Credit and liquidity growth will be slower than last year, but conditions will remain mildly accommodative.

But RRR hikes will continue

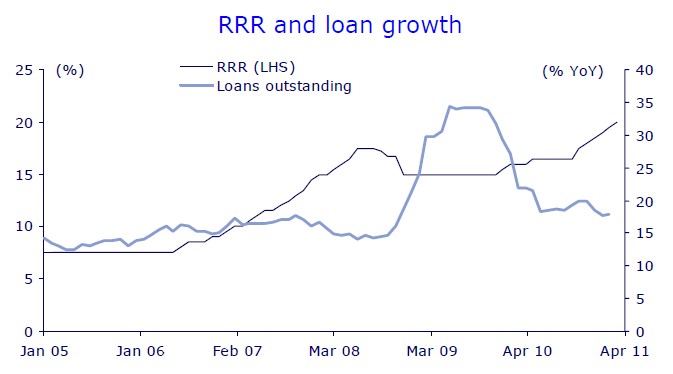

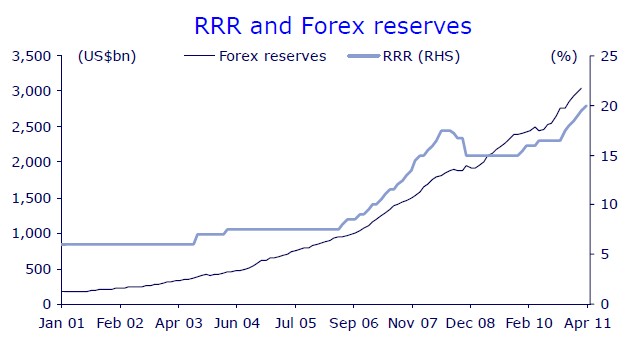

Rate hikes may be over, but the Party will continue raising bank required-reserve ratios (RRR). However, contrary to the way the media describes RRR hikes in China,these steps do not result in monetary tightening and are not targeted primarily at inflation. RRR hikes are used to sterilise increases in foreign-exchange inflows and are thus likely to continue well after CPI peaks in the coming months. But those RRR increases will not squeeze lending or liquidity in China.

RRR in a fake banking system

In a real banking system, regulators use the RRR to manage growth of lending and money supply. Banks only influence the supply of money in an economy when they lend, and a higher RRR lowers the share of deposits that can be lent.

But China does not have a real banking system. All Chinese banks are controlled, via the personnel system - even down to the branch level - by the Communist Party, which also sets interest rates. This enables the Party to set loan quotas for each bank, governing the level of lending above and beyond the RRR limitations. The system works, because any banker who ignores his quota would soon be unemployed.

There is clear evidence that the Party has been successful in controlling lending in this manner. In December 2008, the outstanding-loan growth rate was 18.7% and the RRR was 15%. As the stimulus kicked in and banks were ordered to dramatically ramp up lending, loan growth hit 34.4% in June 2009, while the RRR remained 15%. After the stimulus was withdrawn, loan growth cooled to 18.6% in August 2010, while the RRR rose to only 16.5%.

Across the banking system, as long as deposits continue to rise roughly in line with loans, increases in the RRR have a largely neutral impact, as banks still have enough free cash (deposits) to lend the amount stipulated by their quota. Deposit growth has roughly tracked loan growth, even when real-deposit rates have been negative. (Household deposits rose 18% YoY in 1Q11.) RRR increases also appear to have only a short-term sentiment impact on China’s interbank lending rates.

Could RRR increases constrain lending?

If the Party were to raise the RRR to the point where it locked up so much of the banking system’s deposits that banks did not have enough cash available to lend the full amount assigned under their quota, then RRR hikes could be considered ‘tightening.’

But this raises the question, why would the Party, which sets both the RRR and the loan quota, raise RRR to a level that would leave banks unable to make the amount of loans the Party itself had deemed necessary to support its GDP growth targets? Sounds unlikely, doesn’t it?

So why is the Party raising the RRR?

In recent years, the Party has used RRR increases as a relatively inexpensive option for sterilising foreign-exchange inflows.

Inexpensive because the interest rate that the central bank has to pay commercial banks on their required-reserve deposits is lower than the rate for central bank bills, the other main sterilisation tool.

But if the central bank is simply forcing commercial banks to freeze the new funds, the RRR hikes are maintaining a stable liquidity level at the banks, rather than tightening.

As central bank deputy governor Hu Xiaolian recently explained, ‘Raising RRR is mainly for offsetting the newly-increased liquidity from forex inflows, and this has not had a big impact on the normal liquidity position of financial institutions. The general effect is neutral. Measured from the theoretical and practical analysis, there is still considerable room for future RRR adjustment.’

Investors will have to decide if continued RRR hikes represent tightening, which threatens to slow the economy and corporate profits, or if they should shrug off the RRR increases as they did in 2H07, when the RRR rose 300bps and the A-share index doubled.

Currency

In July 2005, the Chinese government acknowledged that it was time to relax the currency peg and begin a gradual appreciation of the renminbi against the dollar. The central bank said the move was designed to ‘enable the market to fully play its role in resource allocation, as well as to put in place and further strengthen the managed floating exchange-rate regime based on market supply and demand.’ This policy decision was consistent with other recent steps, such as using government control over wholesale and retail energy prices to begin moving those prices closer to apparent market prices.

The central bank also announced that the new ‘managed floating exchange rate regime’ would be ‘based on market supply and demand with reference to a basket of currencies,’ and that the ‘renminbi will no longer be pegged to the US dollar.’ Those changes were never put into place, but the renminbi did begin a steady appreciation against the dollar.

From mid-2005 to mid-2008, the renminbi appreciated 21.2% against the dollar and 15.1% on a real effective basis. Beijing suspended the appreciation process and re-established a defacto dollar peg in the summer of 2008, as China’s exports collapsed and the global financial crisis struck.

At the start of last year, we forecast that ‘Beijing will resume gradual appreciation in mid-2010, when a recovery in Chinese exports will enable Beijing to make a convincing argument to its own people that it is resuming appreciation on its own terms.’ In mid-June, the peg was re-broken, and for the full year the renminbi appreciated 3.1% against the dollar, or an annualised pace of about 6%.

Since the start of the year, the annualised rate of appreciation has been in the 5- 7% range, and that is the pace we expect through next year. We do not believe the higher rate of inflation will lead to a change in exchange-rate policy. Certainly, that has not happened yet. Although March recorded the highest CPI level in 32 months, the annualised appreciation rate each day that month, as well as in April, was within the 3.3-6.3% range.

In our view, the Party does not consider the exchange rate as a tactical tool for managing short-term problems, such as high food prices. Rather, gradually moving the currency towards a market-based equilibrium rate is considered a long-term structural adjustment. This is why the Party did not significantly accelerate the pace of appreciation in 2007 (when both food and oil prices were rising rapidly), nor did it devalue when exports collapsed in 2H08. It is also worth noting that since most of the food inflation is domestic, faster appreciation would have little short-term impact on prices. And a stronger currency is no guarantee of cheaper import prices, as global markets would soon respond by bidding up the price of soybeans and other commodities in line with a rising renminbi.

Regards,

Andy Rothman

China Macro Strategist

CLSA Asia-Pacific Markets

Shanghai

12 May 2011